- Home

- About Us

- Contribute

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Contact Us

Languages

اردوMilitary System

With the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh, Egypt continued to develop over the next three millennia. Its history is composed of a series of stable kingdoms which were separated by periods of relative instability known as the intermediate period. After the golden age of the New Kingdom, Egypt was conquered by a succession of foreign powers, and the rule of the pharaohs officially ended in 31 B.C. when the early Roman Empire conquered it, and made it their province. The ancient Egyptian military forces were well maintained, but the new form, which appeared in the New Kingdom, was more organized. The main aim of the military was to keep the enemies out.

The Nile valley was surrounded by the desert which formed a barrier and kept the incoming massive forces at bay since it was impossible to cross. The nomadic people who resided in this desert, occasionally tried to raid and settle in the fertile Nile valley, but were always repulsed the Egyptian military. Along the eastern and western borders of the Nile delta, the Egyptians built fortresses and outposts which could prevent minor attacks, but if a major force was detected, a message was sent for the main army since the Egyptian cities lacked city walls and other defenses. Apart from defending the territory, the Egyptian military was also involved in merciless conquests of nearby areas which also involved slaying of innocent women and children. Secondly, the army was also used internally for personal political benefits which also resulted in the loss of lives.

Military Activity

The pictorial and archaeological records of late Pre-dynastic Egypt reveal the expansion of small centralized kingdoms in Upper Egypt and provides evidence of overt military activity. 1 Military was an institution that evolved over the centuries as a result of Egypt’s expansion and contact with outside elements. Egypt’s military forces had a definitive role in maintaining the sovereignty of the country from the earliest historical periods and in obtaining natural resources and new lands. 2 Before the Middle Kingdom, the civil and the military were not sharply distinguished. Military forces consisted of local militias under their own officials and included foreigners, and nonmilitary expeditions to extract minerals from the desert or to transport heavy loads through the country were organized in similar fashion. 3

In charge of the professional army was the king, who often led troops into battle himself. However, the king’s vizier actually took on most of the responsibility for a military campaign as minister of war. Also important were princes and generals, who would take charge of military action on the battlefield whenever the king was not present. There was also a hierarchy of lesser commanders, grouped under a lieutenant commander who reported directly to the general. The general who took charge of various divisions and Special Forces of soldiers; the titles of these commanders were usually based on how many men were under their control. 4 An army division had several thousand men, typically 4000 infantry and 1000 chariots, organized into 10 battalions of about 500 soldiers. These were further subdivided into 250 strong companies, platoons of 50 men, and squads of ten men who shared a barracks tent. Each division was named after one of the major gods such as Amun, Re, Ptah, and Seth. 5

Notable Military Personalities

Some individuals have left records of their particular contributions to the armed services in Egypt. All kings were commanders in chief of their troops, but some were especially famous as strategists or warriors. Apart from the early conquerors such as Scorpion and King Menes who used military force to unify Egypt and create a nation, others were notable for their actions against foreign threats. During the Middle Kingdom Senusret III extended Egypt’s control over Nubia and completed a series of fortresses there to subjugate and control the local population. Seqenenre Ta’o II, Kamose, Amosis I, and Amenhotep I fought bravely during the conflict between the Theban rulers and the Hyksos to expel the Hyksos and then to establish the foundations of the Egyptian Empire in Palestine. Under the later kings of Dynasty 18 this policy was extended, and under Tuthmosis I, Tuthmosis III, and Amenhotep II the Egyptian frontiers were fixed in southern Nubia and as far north as the Euphrates River. During Dynasty 19, Sethos I and Ramesses II had to reestablish Egyptian influence in Syria/Palestine. Finally, Ramesses III, Egypt’s last great warrior king, fought a vital although defensive battle to prevent the Sea Peoples from entering the Delta.

Professional Army

After the Hyksos domination of Egypt in Dynasties 15 and 16, the native kings who ruled the country in Dynasty 18 had become very aware of the need for a professional, national army. For the first time the rulers of the New Kingdom were determined to create an outstanding military power that would be able to fight off any future attempts by foreign groups to dominate Egypt. This army, probably started by King Amosis I, was organized on a national basis with professional soldiers as officers. This replaced the earlier arrangements when governors had conscripted soldiers from the local population whenever the king decided to fight or undertake expeditions. One of the main ambitions during Dynasty 18 was to establish and retain an empire, and this underpinned the need for development in the army and navy. 6

The ordinary warriors, the foot soldiers, were inferior to the sailors. The naval men, perhaps sharpened by their more difficult service in the fleet, were young officers. Soon thereafter, the Middle Kingdom word for naval team replaced the more specific term, ‘rowing team’. Evidently, the two were the same. In the civil fleet the commanders of the ships stood over the tutors of the naval teams, but in the military flotilla the captains of the ships directly obeyed the king. That is to say, the captains were directly responsible to the Pharaoh. 7

A military career was one of the few paths to status and wealth for a poor young man. Even common soldiers shared in battle loot, including cattle, weapons, and other items taken from defeated people. Ahmes Penekhbet, a soldier who distinguished himself in battle against the Hyksos and Asiatics, won armbands, bracelets, rings, two golden axes, and two silver axes. He also received the gold of valor—six gold flies and three gold lions—from the king.

Most Egyptians were unwilling to go abroad for military expeditions. They were terrified that if they died outside Egypt, their bodies would not be properly mummified or buried, and the proper prayers and spells would not be said at their funerals (if they even had funerals). If that happened, they would lose their chance at eternal life. So even at the height of empire, much of the army was made up of mercenaries (soldiers for hire) and troops from conquered lands, especially Nubians. Late Period armies were mostly Asiatics and Greeks. Slaves and foreign captives often won their freedom by joining the army. 8

Military Recruitment

In the Middle Kingdom the infantry consisted of two main groups—older foot soldiers and younger, less experienced men. In later times the pattern changed: The infantry included recruits, trained men, and specialized troops. During Dynasty 18 some recruits were drawn from Nubia, and prisoners of war began to be enlisted from the reign of Amenhotep III onward, a practice that was continued under the Ramesside rulers of Dynasty 19. In later periods there were many foreigners in the army, but in the New Kingdom it was customary to recruit soldiers by conscription so that, in the reign of Ramesses II, the proportion of the population who was forced to take up military service numbered one man in every ten.

In addition to conscription there were men who chose the army as a profession, and during the Ramesside Period the upper classes included many military officials. Military service for them offered rapid wealth and promotion, and officers were selected from these professional soldiers. Also, since the king believed that he could rely on the army, he created important palace officials from their number such as the tutor to the royal children. Other incentives to join and remain in the army included the opportunity to gain great wealth by acquiring booty taken during the campaigns—and the law also ensured that land given by the king to his professional soldiers could only be inherited by their sons if they also joined the army. Conscription, recruitment of foreign soldiers, and inducements to join the army, all helped the Egyptian rulers to build a professional army that could establish and control an empire. 9

Military Training

Training in the army started as young as 5 years old, although professional military service didn’t start until the age of 20. Older recruits may have joined as part of a national service with a requirement of serving at least a year before returning to their villages. However, after training they could be called up at any time. 10 New recruits would have their hair cropped very short or their heads shaved bare. Then they were equipped from the quartermasters’ stores with leather body armor, helmets, and leather-covered wooden shields. They were then assigned to a ten-man squad who would share a barrack. The Egyptian soldiers were expected to become competent with a variety of weapons—battle axes, swords, maces, spears, daggers, bows and arrows—but their unit usually specialized in the use of one particular weapon. Some units were given very specialized training such as trench-digging (by sappers), using battering rams and scaling ladders, and scouting.

The training was tough, and young recruits were sent on long marches to prepare them for campaign, when the army often covered an average of 12 miles a day over baking desert terrain. Drilling and discipline was hard. Battles usually consisted of a succession of precisely executed maneuvers, and soldiers were expected to respond promptly to the commands of the trumpeter. 11

Sustenance

Soldiers often had to carry their sustenance with them (thus increasing the weight of their packs). Soldiers were given fewer than ten loaves of bread a day each, which they carried in bags and baskets. This bread (probably more biscuit than bread) would have grown mold, which although unknown to the Egyptians was a form of natural antibiotic. Soldiers also carried the ingredients for making bread if they had access to ovens en route or time to fashion mud ovens while at camp.

Other food items were part of the Egyptian military diet because they stored and travelled well, and included onions, beans, figs, dates, fish, and meat. Many kinds of fruit and meat were dried, but the soldiers also caught fish. Enemy livestock was plundered for meat. Beer may have been brewed on campaign because it didn’t keep for long and Egyptian soldiers could not live without it. At times, they remained intoxicated due to which they used to deal brutally to their enemies and behaved like savages in wars. Soldiers had to carry or steal wine to accompany their meals. Because the quantity of food required for an army was so immense, the military probably stored food at numerous forts along the campaign route.

The armies also made use of food storage in any town or village along the way. In fact, villages may have been legally obligated to help passing armies. Of course, feeding 10,000 men and numerous horses at the drop of a hat may have bankrupted a few of the smaller towns, but the ancient Egyptian armies were least bothered about it since they didn’t care much about the welfare of other people.

Compensation

The food that the military needed to survive formed the majority of their wages. In addition to official wages, soldiers were able to plunder other goodies to give their wealth a boost. Plunder in the form of gold, cattle, and even women was taken from enemy camps after cities had been sacked and regions conquered. The officers obviously got the best of the booty, but ordinary infantry soldiers also returned with full backpacks. A formal system of awards also recognized the bravest soldiers for their work. These awards consisted of golden flies (as a sign of persistence), gold shebyu collars for valour, ‘oyster’ shells of gold or shell, and even property. Not only were the soldiers made wealthy by these gifts, they also received recognition within the Egyptian community for their services.

Weapons

The weapons in the Egyptian army were varied and soldiers did not always own their weapons. Weapons varied from the simple to the complicated to the downright unpleasant. 12

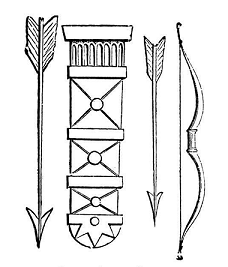

Bow and Arrows

The Egyptian bow, which consisted of two basic parts, the body and the string, was the first tool in history designed to concentrate energy. The bow’s advantage over a mace or sword was its ability to kill at a considerable distance. The earliest Egyptian bows were made from the Acacia tree, one of the few native sources of wood available, and were simply convex in shape. By putting a reverse curve at both ends of the bow— shaping it like an upper lip—the string lay closer to the body of the bow, increasing the distance it traveled when drawn back and hence the amount of tension. This invention armed Egypt’s oldest troops.

The shaft of the arrow was straight, light and strong, and was generally made of wood, occasionally of reed. The arrowhead, which needed to be hard, was made of flint or metal and was either leaf shaped or triangular. The arrow shaft fit into a socket in the head, or else an extension of the head (tang). To ensure that the arrow flew straight, feathers of various birds—eagle, vulture or kite—fletched the end. Because the archer fired many arrows during a single battle, Egyptian leather quivers, holding from twenty to thirty arrows, were worn over the shoulder to free both hands to load and shoot what the Persians called ‘messengers of death.’

Slings

Slings were similar to bows in purpose. Originally designed by shepherds to keep foxes from their herds, these simple weapons composed of a rectangular piece of leather with two strings attached could inflict damage at a distance. A stone was placed on the leather, which became a pouch when the ends of the strings were held together in one hand. The sling was swung round and round to build momentum, then one of the strings was released, which opened the pouch and sent the missile on its way and corps of sling men served in conjunction with archers to rain missiles on massed enemies.

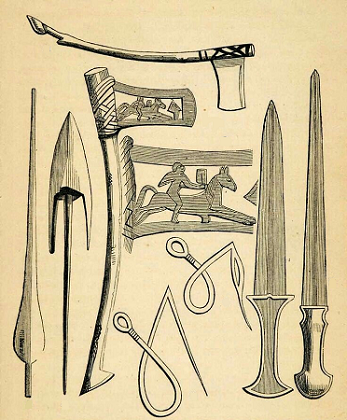

Close Combat Weapons

For closer combat, the arsenal expanded. Javelins were medium range weapons, similar in principle to an arrow but propelled by hand. They consisted of a wooden shaft (approximately five feet long) with a metal tip fixed to it with either a socket or a tang. When hurled by a skilled thrower, javelins could be lethal at more than 100 feet. Spears, larger and heavier than javelins, were intended for thrusting, rather than throwing.

The oldest hand-to-hand weapon was the mace, a simple but lethal weapon which consisted of a stone fixed to the end of a stick whose short handle, about eighteen inches long, allowed quick swings. The lethal end consisted of a carved pear, disc or apple-shaped rock about the size of a fist with a hole in one end for the handle, replacing a modern axe head. Unlike an axe, however, the mace was designed to smash rather than cut. Although it was an impressive weapon, it was replaced by the battle axe when enemies began to protect their heads with metal helmets.

The close combat arsenal also featured lethal-looking but overrated swords. Two basic kinds were employed. A straight version was intended for stabbing so its metal blade was pointed at the tip and honed sharp along both edges. A striking sword, on the other hand, was sharpened only along one edge and curved, like a sickle, to slice as it was pulled back. The problem with both versions was that they consisted of long pieces of bronze which ancient Metal smiths could not forge strongly enough to do damage without bending, chipping or breaking. Battle axes, which evolved over the centuries in response to changes in warfare, were preferred for hand-to-hand combat because they carried a smaller, thicker, more durable metal blade. The first axes were cutting weapons, so their blades were broad, and often curved for a larger cutting surface. The blade was attached to a short wooden handle either by the tang or the socket method and reinforced with cord so it would not fly off during battle. Armor caused the axe’s undoing and cutting blades made no dent in chests of mail or metal helmets. A more pointed blade, better suited for piercing, was developed later. To counteract all these weapons, soldiers carried shields as barriers between themselves and the enemy’s weapon. Soldiers held shields in their left hands to ward off arrows, axes and swords, while attacking with a weapon in their right. Since each country’s shield shape was distinctive, ancient representations of battles distinguish the good guys from the bad not by the color of their hats but by the style of their shields. 13

Egyptian Chariot

Kamose (1555–1550 B.C.) was the first Egyptian ruler to use the chariot and cavalry units successfully. The Hyksos, dominating the northern territories at the time, were startled when the first chariots appeared against them on the field at Nefrusy, led by Kamose. The horses of the period, also introduced to Egypt by the Asiatics, were probably not strong enough to carry the weight of a man over long distances, a situation remedied by the Egyptians within a short time. The horses did pull chariots, however, and they were well trained by the Egyptian military units, especially in the reigns of Tuthmosis, Tuthmosis III, Ramesses II and Ramesses III. These warrior pharaohs made the chariot cavalry units famed throughout the region as they built or maintained the empire. 14

The chariot was a light vehicle, usually on two wheels, drawn by one or more horses, often carrying two standing persons, a driver and a fighter using bow-and-arrow or javelins. The chariot was the supreme military weapon in Eurasia roughly from 1700 B.C. to 500 B.C. It was a moving platform from which soldiers could shoot at enemies. Arrows and javelins were the main weapons used by the fighter on board, while a second person drove the chariot. The tactic was to move constantly, in and out of the battle, shooting from a distance. 15

These vehicles were employed in military and processional events in ancient Egypt, and became a dreaded war symbol of the feared cavalry units. The chariot was not an Egyptian invention but was introduced into the Nile Valley by the Hyksos, or Asiatics, during the Second Intermediate Period (1640–1532 B.C.). Egyptian innovations, however, made the Asiatic chariot lighter, faster, and easier to maneuver. Egyptian chariots were fashioned out of wood, with the frames built well forward of the axle for increased stability. The sides of the chariots were normally made of stretched canvas, reinforced by stucco. The floors were made of leather thongs, interlaced to provide an elastic but firm foundation for the riders.

A single pole, positioned at the center and shaped while still damp, ran from the axle to a yoke that was attached to the saddles of the horses. A girth strap and breast harness kept the pole secure while the vehicle was in motion. Originally, the two wheels of the chariot each had four spokes; later six were introduced. These were made of separate pieces of wood glued together and then bound in leather straps.

Mercenaries

The use of mercenaries was important in the Egyptian army. In the Old and Middle Kingdoms, the army consisted of the militia of the individual nomes or districts, co-opted when required to assist the small national standing army. In the New Kingdom, however, mercenary troops became a significant element in the new professional army. The Medjay (from tribes of Nubian nomads) were engaged to serve in the army and in the internal police force; onetime prisoners of war or enemies, such as the Sherden and Libyans, also became Egyptian soldiers. Numerically, they were so significant that chiefs or captains were appointed to control them and direct their work. In fact, by the late New Kingdom, foreign mercenaries probably formed the major part of the Egyptian army. Even in the reign of Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten) the king’s personal bodyguard included Nubians, Libyans, and Syrians. From the end of Dynasty 18 down to Dynasty 20, foreign officers and troops were given preference over native troops. Considerable numbers of conquered soldiers from the coalition of Sea Peoples and Libyans (the Sherden, Kehek, and Meshwesh) entered the Egyptian army from Dynasty 19 onward. They fought under their own chiefs within the Egyptian army, and in the wars of the Sea Peoples and Libyans against Merenptah and Ramesses III members of some of these tribes fought on both sides.

Later, the descendants of these Libyan mercenaries became the rulers of Egypt in Dynasties 22 and 23. In the period from Dynasty 26 to 30 the Egyptian kings employed mercenaries from Greece and Caria to support their rule and to introduce new ideas and techniques into the army and navy.

Police Force

The police force was not part of the army. It existed to uphold the established order as handed down by the gods and to protect the weak against the strong. The rural police had many duties. They guarded farmers against theft and attack and used persuasion and even physical force to make the peasants pay their taxes. Tomb scenes show how punishment was exacted for nonpayment or cheating: The culprit was forced to lie prostrate on the ground and was beaten by the policeman. They generally upheld order and ensured that troublemakers were sent away from local communities.

Other police forces patrolled the desert frontiers using dogs to hunt out troublesome nomads or escaped prisoners. In Dynasty 18 the Medjay (Nubian nomads who had been known to the Egyptians as early as the Old and Middle Kingdoms) were enrolled in the Egyptian police force and given the duty of protecting towns in Egypt, especially in the area of western Thebes. During an earlier period, the Medjay had been engaged as mercenaries in the Egyptian army when they helped to expel the Hyksos; now working as policemen they were well organized and quickly became absorbed into Egyptian society.

At Thebes the records of the royal necropolis workmen’s town at Deir el-Medina provide details of the Medjay’s role as guardians of the royal tomb during its construction. There were probably eight of them; their main duty was to secure the tomb, and they were responsible to the mayor of western Thebes. The Medjay were also required to ensure the good conduct of the workmen, and to protect them whenever necessary from dangers, such as the Libyan incursions that threatened the community in the late New Kingdom. The Medjay’s other duties included interrogating thieves, inflicting punishments, inspecting the tomb, acting as witnesses for various administrative functions, and bringing messages and official letters. Sometimes they were asked to help the official workforce and assist with the transport of stone blocks.

Although the Medjay were closely associated with the community at Deir el-Medina, they never resided in the village; they lived on the west bank between the Temple of Sethos I at Qurna and the Temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu. Nor were they buried in the royal workmen’s cemetery. This distinction may have existed to ensure that they kept their independence and could be impartial in their dealings with the community. The police force of the west bank was certainly involved in capturing thieves who participated in robbing the royal tombs. Some were local people, but others came from neighboring areas; most were low-ranking officials (including priests and scribes), and they were probably helped by their wives, who were also arrested.

The stolen property was sold, but one thief was displeased with his share and consequently reported his comrades to the police. The police undoubtedly played an important role in bringing people to justice and maintaining law and order. 16 They were allowed to inflict beatings on culprits as a normal punishment for minor offenses, but they also used to take bribes and mishandled the situations to gain benefits from the elite. Some were so corrupt that they used to give relaxations to their friends and families and punished others brutally.

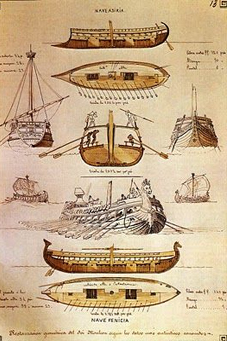

Navy

The first king who recognized the true importance of a navy was Rameses III (twentieth dynasty), and he established a fleet in the Mediterranean and another in the Red Sea. 17 Understanding Egyptian sea power required an understanding of the people who served in the Egyptian maritime forces. Mariners often had special customs, traditions and a distinct language that creates a distinction between them (the people of the seas) and the rest of the societies to which they belong (the people of the land). 18

The navy was an extension of the army. Its main role was to transport troops and supplies over long distances, although on rare occasions it engaged in active warfare. The sailors were not actually a separate force but acted as soldiers at sea. The two services were so closely associated that an individual could be promoted from the army to the navy and vice versa. During Dynasty 18 the navy played an important role in the Syrian campaigns, when Egypt was establishing and consolidating an empire, and again in Dynasty 20 when the Egyptians repelled the Sea Peoples and their allies. Essentially, however, in wartime the navy was regarded as a transport service for the army and a means of maintaining the bases that the army had set up; in peacetime it made a significant contribution to the development of trading links.

Inscriptional evidence provides useful details about the navy. The record relates that vessels were used as mobile bases for military operations in driving out the Hyksos. A wall relief in the Temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu also indicates that ships were used for fighting as well as for transport. Reliefs in Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri, Thebes, provide a vivid, illustrated account of the great expedition to Punt via the Red Sea, which occurred during this queen’s reign. The Gebel Barkal stela is inscribed with the information that ships were built every year at Byblos on the Syrian coast and sent with other tribute to Egypt. Thus, the Egyptians were able to take possession of a regular supply of excellent vessels even though their own country was deficient in building timber.

Byblos also played an important part in supplying the boats that Tuthmosis III took overland to cross the river Euphrates in his campaigns against the Mitannians. He also used ships during his sixth campaign to Syria/Palestine to transport some of his troops to the coastal area, and in his next campaign he sailed along the coastal cities of Phoenicia where he proceeded from one harbor to the next, subduing them and demanding supplies for his troops for their next onslaught. Subsequently, these harbors were regularly inspected and equipped to ensure that they would provide support for the king when he marched inland to extend his attacks against the Mitannians.

Naval Structure

Most information about the organization of the royal navy comes from the Nauri Decree and various biographies of officials. These indicate that the recruits were professional sailors, often the sons of military families. They usually served on warships. At first, they were assigned to training crews directed by a standard-bearer of a training crew of rowers, and then they progressed to join the crew of a ship. No exact information is available about the number in each crew, but this appears to have varied from ship to ship.

On board the sailors were responsible to the commander of rowers; his superior was the standard-bearer. Navigation, however, was under the control of the ship’s captain and the captain’s mates. Their overseer, the chief of ship’s captains, probably commanded several ships. Above the standard-bearer was the commander of troops, a title usually held by older men; this seems to have been an appointment with land-based duties rather than active seagoing duties. At the pinnacle of the naval hierarchy were the admirals, responsible to the commander in chief (the crown prince), who in turn answered directly to the king.

Conditions of service for soldiers and sailors varied greatly, and some literary texts describe the miseries of their lives. In contrast to the tough physical conditions they often had to endure, however, there were compensations. In the New Kingdom, they enjoyed many rewards including access to booty from campaigns, income from their estates, exemption from taxes, and in some cases royal rewards of gold for their bravery. 19

Warship

Egyptian ships had both oars and sails, being fitted with a bipod (inverted V) mast and a single, large and square sail. The whole mast could be lowered when under oars. Large Egyptian ships had more than 20 oars to a side, with two or more steering oars. The war galley was built to the same pattern but was of stouter construction. Modifications that could be easily incorporated in a merchant ship’s hull under construction included elevated decks fore and aft for archers and spearmen, planks fitted to the gunwales to protect the rowers, and a small fighting top high on the mast to accommodate several archers. Some galleys had a projecting ram, well above the waterline, which may have been designed to crash through the gunwale of a foe, ride up on deck, and swamp or capsize him. 20

Two Decisive Battles

Battle of MegiddoEgypt's main rival in the first half of the Eighteenth Dynasty was Mitanni, a kingdom sandwiched between the growing powers of Hatti and Assyria. By the time of Tuthmosis III Mitanni had established itself as the dominant influence on the city-states of Syria. During the reign of Tuthmosis III's stepmother, Hatshepsut, there had apparently been no Egyptian military campaigns in Western Asia, and the conquests of his grandfather, Tuthmosis I (who had placed a boundary stele as far north as the bank of the Euphrates), were being rapidly whittled away.

In about 1503 B.C., less than a year after he came to the throne, Tuthrnosis III embarked on his first, and perhaps most significant, expedition in order to thwart a 'revolt' of city-states led by the prince of Qadesh and doubtless backed by Mitanni, He marched his army from the eastern Nile Delta, via Gaza and Yemma, to the plain of Esdraelon, leaving his general Djehuty to lay siege to the town of Joppa (modern Jaffa). According to a legend preserved on the Rammeside Papyrus Harris 500 at the British Museum, Djehuty's men, like Ali Baba, were smuggled into Joppa inside baskets. Whatever the truth of this story, Djehuty himself was a historical character and his tomb at Thebes contains an inscription describing his role in the campaign.

When Tuthmosis III arrived at Yemma he was informed that the enemy were waiting for him on the far side of the Carmel ridge, using the city of Megiddo as their base. A council of war then took place between the king and his generals. There appear to have been three possible strategies: to follow the most direct route across the ridge, emerging about 1.5 km (l mile) from Megiddo; to take the path northwards to the town or Djerty, emerging to the west of Megiddo; or to take the more southerly route via the town of Taanach, about 8 km (5 miles) south-east of Megiddo. The king chose the most dangerous approach - the direct route - which would take the army through a narrow pass, forcing them to march slowly one after the other, relying solely on the element of surprise.

The journey across the Carmel range took three days, ending with a lengthy but safe passage through the narrow defile. The army then descended on to the plain, and immediately found itself within a few hundred meters of the confederation of Asiatic troops encamped for the night in front or the city of Megiddo. The following morning Tuthmosis III's troops launched a frontal attack that routed the enemy, described as 'millions of men, hundreds or thousands of the greatest of all lands, standing in their chariots'. In their haste to take shelter in Megiddo, the fleeing troops were said to have accidentally locked out the kings of Kadesh and Megiddo, who had to be dragged on to the battlements by their clothing. After a seven-month siege the city was captured, bringing the campaign to a successful conclusion. 21

Battle of Kadesh

The final and decisive Egyptian battle in Asia, a turning point equal to that of Megiddo under Thutmose III, took place in year five of Ramesses II at the city of Kadesh in central Syria. 22 The Battle of Kadesh (1275 B.C.), was a major battle between the Egyptians under Ramses II and the Hittites under Muwatallis, in Syria, southwest of Ḥomṣ, on the Orontes River.

In one of the world’s largest chariot battles, fought beside the Orontes River, Pharaoh Ramses II sought to wrest Syria from the Hittites and recapture the Hittite-held city of Kadesh. There was a day of carnage as some 5,000 chariots charged into the fray, but no outright victor. The battle led to the world’s first recorded peace treaty.

Resolved to pursue the expansionist policy introduced by his father, Seti I, Ramses invaded Hittite territories in Palestine and pushed on into Syria. Near the Orontes River, his soldiers captured two men who said they were deserters from the Hittite force, which now lay some way off, outside Aleppo. This was reassuring, since the impetuous pharaoh had pushed well ahead of his main army with an advance guard of 20,000 infantry and 2,000 chariots. Unfortunately, the deserters were loyal agents of his enemy. Led by their High Prince, Muwatallis, the Hittites were at hand—with 40,000 foot soldiers and 3,000 chariots—and swiftly attacked. Their heavy, three-horse chariots smashed into the Egyptian vanguard, scattering its lighter chariots and the ranks behind. An easy victory seemed assured, and the Hittites dropped their guard and set about plundering their fallen enemy. Calm and determined, Ramses quickly remarshaled his men and launched a counterattack.

With their shock advantage gone, the Hittite chariots seemed slow and ungainly; the lighter Egyptian vehicles outmaneuvered them with ease. Ramses, bold and decisive, managed to pluck from the jaws of defeat if not victory, then at least an honorable draw. Both sides claimed Kadesh as a triumph, and Ramses had his temples festooned with celebratory reliefs. In truth, the outcome was inconclusive. So much so that, fifteen years later, the two sides returned to Kadesh to agree to a nonaggression pact—the first known example in history. 23

Military Decline

With the onset of economic and political decline, the last battles of the native Egyptian pharaohs were desperate defensive struggles, far removed from the empire building of Sesostris III, Tuthmosis III and Ramesses II in the Middle and New Kingdoms. Many of the military actions of the Third Intermediate Period and Late Period took place on Egyptian soil, as successive waves of foreigners capitalized on the weakness of their old enemy. As with any such decline, it is difficult to pinpoint the precise causes of this new vulnerability. In the economic sphere, Egypt had become less self-sufficient in metals particularly with the increasing importance of iron, all of which had to be imported, producing a dangerous dependence on trade with Western Asia just at the time when Egyptian influence in the Levant was at its lowest ebb. In the purely military sphere, there is growing evidence that native Egyptians were once more gravitating towards the traditional religious and bureaucratic routes to power, leaving the Egyptian army dangerously dominated by foreign mercenaries and immigrants.

Eventually the campaigning of the Kushite (Twenty-fifth Dynasty) pharaohs in Syria-Palestine led to direct conflict with a new imperial power: the Assyrians. In 674 B.C. Taharqa (ruled 690-664 B.C.) was temporarily able to deter the invading forces of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon (ruled 680-669 B.C.), but in the ensuing decade, the Assyrians made repeated successful incursions into the heart of Egypt, and only the periodic rebellions of the Meeks and Scythians -at the other end of the Assyrian empire -prevented them from gaining a more permanent grip on the Nile valley.

During the Late Period, the Egyptians found that they themselves were not exempt from their current cycle of conquest, pillage, vassaldom and rebellion that had for so long been endemic in the Levant. Once they had been defeated by the Assyrians, their status was effectively reduced to that of the Syro-Palestinian princedoms, and the myth of Egyptian military supremacy could no longer be sustained. 24 Hence it was during this period that the military supremacy of Egypt was destroyed.

The ancient Egyptian military was more focused in expanding the empire and personal wealth through war bounties in the form of gold, silver, slaves and concubines rather than focusing on the welfare of the conquered people as well. Even though those armies were great in some areas, but all lacked ethics and had no specified humane rules of war whereas the ethics, morality and the high standard of professionalism shown by those who had submitted to the will of God was exemplary. The Muslims never attacked to gain war bounty or land, but to establish peace, justice and prosperity and root out the tyrannical and unjust rulers. This was the reason that even the non-Muslims preferred to live under Muslim rule rather than the people of their own religion. All of this can be seen in the books of history where the ethics, humanity and morality of the Muslim armies have been praised through the ages.

- 1 Allan B. Lloyd (2010), A Companion to Ancient Egypt, Blackwell Publishing, Sussex, U.K., Vol. 1, Pg. 425.

- 2 Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 244.

- 3 Kathleen Kuiper (2011), The Britannica Guide to Ancient Civilizations: Ancient Egypt, Britannica Educational Publishing, New York, USA, Pg. 24.

- 4 Patricia Netzley (2003), The Green Haven Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Green Haven Press, Michigan, USA, Pg. 198.

- 5 Norman Bancroft Hunt (2009), Living in Ancient Egypt, Chelsea House Publishers, New York, USA, Pg. 71.

- 6 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 271-273.

- 7 Anthony J. Spalinger (2005), War in Ancient Egypt, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, U.K.., Pg. 5.

- 8 Wendy Christensen (2009), Empire of Ancient Egypt, Chelsea House Publishers, New York, USA, Pg. 87.

- 9 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 271-272.

- 10 Charlotte Booth (2007), The Ancient Egyptians for Dummies, John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Sussex, U.K.., Pg. 67.

- 11 Norman Bancroft Hunt (2009), Living in Ancient Egypt, Chelsea House Publishers, New York, USA, Pg. 70-71.

- 12 Charlotte Booth (2007), The Ancient Egyptians for Dummies, John Wiley & Sons Ltd., Sussex, U.K.., Pg. 71-73.

- 13 Bob Brier & Hoyt Hobbs (2008), Daily Life of the Ancient Egyptians, Green Wood Press, West Port, USA, Pg. 249-253.

- 14 Margaret R. Bunson (2002), Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 81-82.

- 15 Ancient History Encyclopedia (Online Version):http://www.ancient.eu/chariot/ : Retrieved: 19-06-2017

- 16 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 274-275.

- 17 E. A Wallis Budge (1914), A Short History of the Egyptian People, E. P. Dutton & Co., New York, USA, Pg. 199.

- 18 Gregory P. Gilbert (2008), Ancient Egyptian Sea Power and the Origin of Maritime Forces, Sea Power Center, Canberra, Australia, Pg. 17.

- 19 Rosalie David (2003), Handbook to Life in Ancient Egypt, Facts on File Inc., New York, USA, Pg. 289-290.

- 20 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/technology/naval-ship : Retrieved: 29-07-2017

- 21 Ian Shaw (1991), Egyptian Warfare and Weapons, Shire Publications, Buckinghamshire, U.K.., Pg. 47-49.

- 22 Anthony J. Spalinger (2005), War in Ancient Egypt, Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, U.K.., Pg. 209.

- 23 Encyclopedia Britannica (Online Version): https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Kadesh : Retrieved: 29-07-2017

- 24 Ian Shaw (1991), Egyptian Warfare and Weapons, Shire Publications, Buckinghamshire, U.K.., Pg. 66-67.